The first lines.

- Home, index, site details

- Australia 1901-1988

- New South Wales

- Overview of NSW

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Queensland

- Overview of Qld

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- South Australia

- Overview of SA

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Tasmania

- Overview of Tasmania

- General developments

- Reports

- Organisation

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Railway lines

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Overview of Tasmania

- Victoria

- Overview of Vic.

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Ephemera

- Western Australia

- Overview of WA

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

The beginning of telegraphic communication in Victoria.

The beginning of telegraphic communication in Victoria cannot be placed on the shoulders of one man - it was simply such a major and innovative undertaking. As a precursor to such a radical social and economic change, the environment must be conducive to the acceptance of the enterprise and the development of the proper climate involves a number of far-sighted individuals. Two of these will be identified here although there are many.

Hugh Culling Eardley Childers arrived in Melbourne in 1850. In the following year, he became a member of the first Victorian Government and he was made Auditor-General in 1852. He was instrumental in helping to found Melbourne University and assisted in its management from 1853 to 1859.

In 1853, Childers asked Lieutenant Governor Latrobe to permit him to put a sum on the Estimates for constructing a telegraph line from Melbourne to Port Phillip Heads. Such a line would be useful for telegraphing news of the arrival of ships. Childers believed that construction of a telegraph was too important to be left to a private company. His proposal met with opposition in the Council and was refused.

Meanwhile, late in 1852, an American named Samuel McGowan arrived in Australia after having worked with several Canadian and American telegraphic companies. Prior to those experiences, he had also worked with Samuel Morse. He came to Australia with the explicit intention of establishing the telegraph. He brought with him a telegraphist and a large quantity of telegraphic equipment.

McGowan had discussions with many people both in Victoria and elsewhere. Naturally, one of the most influential was Hugh Childers. During their discussions, in the first half of 1853, Childers asked McGowan to build an experimental line from the old Audit Office in Lonsdale Street to the principal buildings in Melbourne. This line was actually the first line in the southern hemisphere. He then asked members of the Legislative Council to come and see it at work. They were immediately convinced of the power of the new technology and, soon after, the Telegraph Department was established. The Age newspaper also witnessed the demonstration and became a significant supporter.

McGowan still wished to construct a longer telegraph line - and of course own the mechanism of such communication. Before he could begin construction to demonstrate his expertise however, the Colonial Victorian Government advertised a contract to construct a telegraphic line from the Government Offices in Melbourne to the signal Station at Gellibrand Point, Williamstown - a distance of about 10 miles. McGowan was told (in the nicest way of course) that, if he continued independently of the Government, the contract would be awarded to someone else. Soon after, McGowan decided the Government was proceeding in absolutely the correct way and he was delighted to be awarded the contract - which would enable him to achieve his own personal ambitions but in a different way. Thus began an era (which never really ended) of Australian Governments not wanting commercial and private interests associated with telegraphic communication. It was a pattern repeated in almost every Australian Colony.

Construction of the Williamstown line began on 19 November 1853. The Williamstown Telegraph Office was constructed on Point Gellibrand. The line took time to build because labour was expensive. The electric wire was hung from poles about twenty feet high from the ground and took a westerly direction from Williamstown along the north bank of the Yarra River. It then followed "a rather circuitous route by the north-west" until it reached the Custom House in Melbourne where a temporary office had been set aside at the rear.

The line was "placed in operation" in February but not opened for business to the public by Governor La Trobe until 3 March 1854 due to a shortage of office space. Even then however, the line was without charge to the users until 1 May when the Electric Telegraph Act 17 Victoria, No. 22 was introduced. A detailed account of the operation and the equipment is reproduced elsewhere.

On 17 April 1954, Tenders were called (see for example The Argus, p 3) for the supply of 1,000 telegraph poles either round saplings or solid timber sawed square. In addition to further information about the poles, the advertisement requested that 500 poles be delivered to each of Williamstown and Geelong.

The line was used almost immediately for operational purposes. For example, the Shipping Gazette and Sydney General Trade List of 12 June 1854 carried the information "Masters of vessels are recommended to have ready a summary in triplicate of the latest and most important intelligence they may be in possession of, for the purpose of affording the public early information. A copy should be given to the boarding officer for transmission by the electric telegraph, a branch of which is in full operation between Melbourne and Williamstown, and is immediately to be extended to Geelong and the Heads".

As the Colonial Government had confirmed its decision that the lines in the Colony would be a Government responsibility, the position of Superintendent of the Electric Telegraph was immediately offered to McGowan.

It was not long before an incident occurred which was not only "perhaps the greatest demonstration of excitement that has ever been known to occur in Melbourne" but it highlighted an operational problem which would later face telegraph operation in all Colonies. On the night of 7 September 1854, events led to the population of Melbourne turning out because of a rumoured invasion by the Russians. "All that could go, did. The deaf went to see, and the blind to hear. The quidnunc went to seek his pabulum and the mare's-nester to expound to any listener he could find the mystery at which all were agape". The suspicions turned out to be ill founded. During the height of the anxiety, the (Melbourne) Telegraph Office "was in a state of siege; the clerk in charge who, having done his day's work, was out enjoying the evening balmy, returned in haste, set his batteries to work, and made his corrections, but found, to the general disappointment, that there was no circuit, for the Williamstown station was unoccupied. He remained on the watch for some time, but at last, as things became quieter, retired to rest" (page 2). There would be several other incidents in which lives were lost because of major telegraph offices not being staffed at night.

The Supplementary Estimates of Expenditure submitted to the Legislative Council in November 1854 contained an estimate of £15, 014/ 1/ 0 for the Electric Telegraph including a line to Shortland's Bluff (Queenscliff).

|

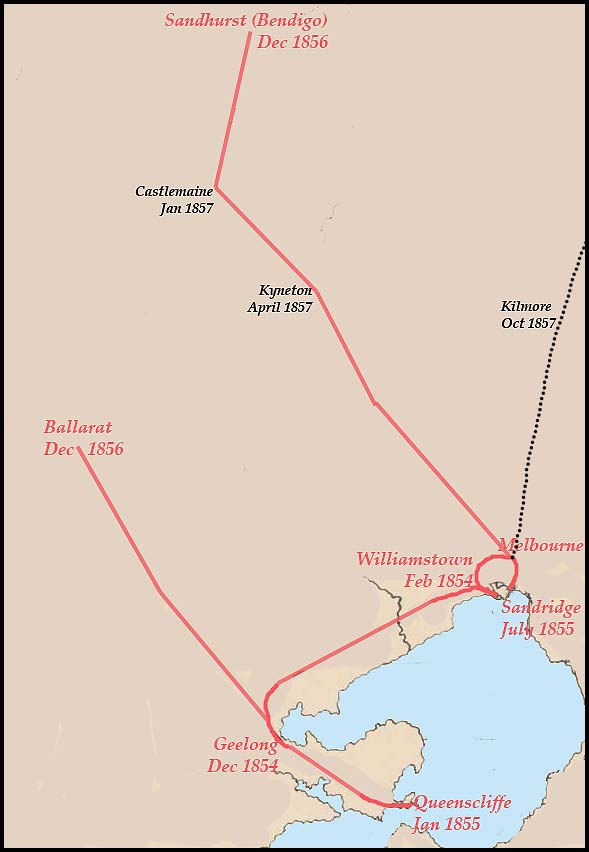

Work began soon after to extend the line - although Telegraph Offices were ready in few places. Over the next year, the line ran:

|

In July 1855, at the completion of these construction activities, Victoria had 72 miles of telegraph line. After a short pause, it was decided to extend the existing lines to the north:

- from Geelong to "Ballaarat" (14 December 1856). Gold had been discovered at Ballaarat in August 1851 and in 1856, there were nearly 30,000 people working in the area. The name Ballaarat was used from 1837 but officially shortened to Ballarat in 1996.

- from Melbourne to Sandhurst (20 December 1856). Up to 1 January 1854, Sandhurst had been known as Bendigo Creek.

Much later, on 18 May 1891, Sandhurst changed in name to Bendigo after a poll had been conducted by the City Council. From 1851, when gold was discovered, there had been a big influx of miners from around the world. Coach transport began to Sandhurst in 1853 but it was the opening of the telegraph line which significantly altered communications especially with Melbourne.

McGowan was apologetic in his Report to both Houses of Parliament (December 1856) for the slow completion time of the two northern lines but he noted that "owing to the inclemency of the succeeding three months (after May) and the nearly impassable state of the roads, progress was necessarily retarded. I feel gratified however in being able to state that notwithstanding the difficulties which have presented themselves, both lines have been completed in a period little exceeding six months" (p. 9).

McGowan also foreshadowed, in his 1856 Report, that "Stations will be established at Sandhurst, Castlemaine, Kyneton and Gisborne with the least possible delay and I anticipate having the permanent communication open with these places almost immediately" (p.9). The Telegraph Offices at the first three were opened by April 1857.

By 1857 the electric telegraph had replaced the system of signalling flags on Flagstaff Hill employed to disseminate shipping intelligence

In September 1858, a second wire was erected between Geelong and 'Ballaarat' "to provide an additional facility for the transmission of messages destined for places beyond the western limit of the Colony i.e. between Melbourne and Mount Gambier in South Australia via Beaufort, Streatham, Hexham, Warrnambool, Belfast and Portland" - see elsewhere for this route.

It is interesting to obtain insight into the prevailing situation at the time. The Bendigo Advertiser of 30 January 1857 published the following:

INTERRUPTIONS TO TELEGRAPHIC COMMUNICATIONS.

"Dr. Owens put a very pertinent question to the Government in the House on Tuesday with reference to the Electric Telegraph, which Mr. Childers answered in that jaunty style so offensive to good taste, inasmuch as it shows that the speaker is thinking more of the manner than of the matter of his remarks.

Now we beg that Mr. Childers would understand that this subject is really one of great interest to that portion of the public professed to be served by the erection of the line of telegraph to Castlemaine and Bendigo. We freely admit that the expeditious establishment of electric communication with three great goldfields has been most creditable to the Government and there can be no doubt that it is fully appreciated by the public, who understand the value of material advantages in the shape of public works much better than less material improvements of much greater importance.

But having experienced the benefits of the telegraph, they feel more keenly its suspension. Indeed, they have a right to complain of the irregularity, consequent upon such suspension, for it may entail very serious difficulty and loss. If we are to have telegraphic communication, let us have it perfect or not at all. During the very short time that has elapsed since the line with Sandhurst has been opened, communication has been suspended some four or five times. The last suspension has been for two or three days.

Now there seems to be no end to this sort of thing. On the first occasion of interruption, we were promised that such inconveniences would be very rare and we were assured that they only occurred immediately after the opening of a line. The evil, however, instead of becoming less, has grown greater, and really, if the present irregularities are likely to continue for any length of time, it would be as well to suspend communication altogether until the line is put in such a state as to be free from these interruptions,

When Mr. Childers spoke with such levity of the waywardness of bullock drivers, who would drive against the telegraph posts, being the reason why the line was out of order, Dr. Owens very justly retorted that it appeared to him to be the fault of the Government to have posts erected at the mercy of every erratic vehicle. We have it on the best authority that, on Keilor Plains, the posts are without the slightest protection and the various roads cross and re-cross hundreds of times the line of posts. On the plains near the Gap, the result is very apparent for some half dozen posts are knocked at various angles from the perpendicular and, in one place, on Monday last, the wire had fallen nearly to the ground from the post which should have upheld it. The tracks of wheels might be observed so near the various posts that it ceased to be a wonder how the latter came to be knocked down, and it is only a matter of surprise, considering the number of vehicles on the road, how communication can be maintained for a few hours together. Along the greater portion of the road, the line of posts is protected by a ditch cut parallel between it and the road. Why is this not done throughout—or if there is any difficulty in cutting a trench on the plains, there would be none in finding large stones to place at the foot of the posts and thus keep off the bullock teams and American wagons which at present do such damage. As the Government have gone to the expense of a telegraph line, they might as well go to the expense of making it serviceable.

Mr. Childers stated that it was the intention of the Government to prosecute with rigor any person found guilty of knocking down the telegraph posts and that placards were being circulated offering rewards for the conviction of all offenders in this way. This is very well in its way, but it should be accompanied with precautionary measures against the evils complained of. The line of posts must be protected throughout against such accidents by the cutting of a deep trench and it must be placed under proper supervision. If this is not done, the accidents will still continue and, although an example being made of some reckless offender would do good, it will not be effectual in wholly preventing interruptions which cause very great inconvenience".

Footnote: The first circuit arrangement was a simplex one but, about 1857, Duplex working was introduced and the output was correspondingly increased. On the Melbourne-Geelong-Queenscliff line, "closed circuit" morse working was adopted, the signals being transmitted by interrupted current. The lines consisted on galvanised iron wire No. 6 S.W.G and the batteries, both main and local, consisted of an early form of Grove cell (extracted from Crawford (1934)).

It was not long before the traffic built up especially between Melbourne and the Heads. The Geelong Advertiser of 4 August 1859 noted as follows:

"M. 59-1G7S.

General Post Office, Melbourne,

July 20th, 1859.

Sir, Adverting to your communication of the 8th instant, I am directed by the Postmaster-General to state, for the information of the Melbourne Chamber of Commerce, that provision will be taken on the Estimates 1860, for some additional facilities for the transmission of intelligence by electric telegraph between the Heads and Melbourne on the Lord's Day".